TaleSpin, the Thirties and Healthy Masculinity

Why a dumb cartoon bear is an unlikely male ideal

The allure of a lost world

Lately I’ve become more and more fascinated with the twenties and thirties. The old twenties, I suppose we should say, since we’ve finally reached that strange point where we’ve caught up with the twentieth century and ‘the twenties’ is just the present day.

Anyway, there’s something enticing about the interwar years for me. Don’t get me wrong: I don’t mean to overly romanticize them. This was a time of vast, jaw-dropping injustice and inequality, and also the time where all the seeds of our current predicaments were sown. No one should ever have to live through an era like the Great Depression, made so much worse by the needless greed and cruelty by those who had more than enough.

In spite of this, there’s a sense of class and elegance to the era we just don’t see these days. Even industrial objects could still be made with a sense of beauty and refinement to them. Compare, say, a modern industrial park to the factories and public architecture of the pre-war era. Isn’t it a paradox how we’re probably at the all-time peak of material wealth our species will ever see, but we’re incapable of building anything but ugly boxes made for maximum profit at minimum expense and nothing else?

My fascination with the time isn’t simply about aesthetics, though. People back then were serious, in a way we simply aren’t anymore. I’ve started saying, in that half-joking way that isn’t that much of a joke, that one of the biggest reasons we’re in so much trouble as a culture these days is that there’s no one around anymore who remembers the 1930s. While I’m not at all sure real history is as simple as the “hard times-strong men-good times-weak men-hard times” macho meme, there’s no question living with that kind of deprivation gives a perspective on life we can’t appreciate in our much more decadent age. Right at the point where peak oil and peak everything starts to bite and we really could use the experience of people who knew how to make the absolute most of very meager resources, they’re all gone. Figures, doesn’t it?

People back then seem to have been able to grasp nuance, complex arguments, trade-offs and long-term thinking in a way that seems out of reach for most decision makers in our increasingly clownish world today. What’s more, they actually stood for something. Back then, pre-industrial life was in living memory. The whole industrial project and modernity had a purpose. I’d personally find many of the convictions they held abhorrent. Still, at least they held them, and when they chewed up the natural world to make way for the industrial project, it was a genuine vision of human betterment and destiny, if a misguided one. These days we’re just robotically growing the GDP way past the point where it makes any sense, because it’s what we’ve always done and we can’t imagine anything else. On top of being self-destructive and ecocidal, that’s just sad.

You’re not here to listen to me rant about all that stuff, though. It’s all been said eloquently a hundred times over by the likes of John Michael Greer, Chris Smaje, David Fleming and William Catton, just to name a few of my personal faves. Instead I’d rather talk about fiction. It so happens that the 1930s have some important points in their favor as a setting for stories too, so let’s start the pivot towards the real subject of this entry by looking at them.

Of course the cool aesthetics are, again, a major plus. You’ve got most of the technologies we use today already in place, but with cooler-looking and somewhat exotic versions to our eyes.

In fiction we can appreciate that without having to live with their drawbacks, so it’s a win-win. Following from this, it’s a world that’s both very recognizable and very different. It’s like seeing our own time reflected in the ripples of a forest lake. We can easily see ourselves there, relating to these people, but it’s also very much a foreign country.

The point about modernity being in its infancy also applies here. There are so many frontiers, technological, social and geographical. Most of the world is explored, but there are still unknown corners, still room for real mystery. You can have a modern mindset, more or less, up against relics of the pre-industrial age. Borders and bureaucracy could be sidestepped much more easily than today. It’s an ideal playground for adventure. Well, as long as you’re wealthy and privileged, anyway.

In this essay, I’d like to dig into an old show that takes advantage of all this to great effect. A show that presents a sanitized but still exciting vision of this era, while allowing the real ugliness of poverty and abandoned children to peek in through the door at times. And also a show that has some surprisingly nuanced and thoughtful things to say about masculinity and fatherhood, for a cartoon.

Yes, as you’ll know from the title, we’re visiting the thirties by way of the early nineties to take a closer look at Disney’s TaleSpin.

A surplus of jerks

‘Toxic masculinity’ has been a bit of a buzzword for a while now. Of course that’s partly because it’s one of the favorite cudgels for the perpetually offended to bludgeon their enemies with. Sure, but I also think it’s a real thing that deserves a label. On this side of the 2010s it’s easy to forget all the obnoxious chest-thumping machismo that actually did exist in the twentieth century, and that’s still alive and well in many places to this day. For all the talk about toxic masculinity, though, it feels like we don’t hear about its opposite very often. That’s a bit of a shame because it’s clear that a lot of men and boys aren’t having a great time of it in our cultures, to put it mildly, and if we’ve ever needed a robust selection of healthy masculinities to choose from, it’s now.

TaleSpin gives us a very good portrait of one such genuinely healthy masculinity. In the form, yes, of a dumb cartoon bear. I don’t care. Unlikely as it sounds, I think Baloo (Ed Gilbert) is one of the best dads in popular fiction, and also a great example of a man who’s allowed to be traditionally masculine but also nurturing and emotionally healthy. He's flawed, but in ways that tends to make him sympathetic and relatable, and at his best he pushes himself to rise above them.

One objection here might be that he's an idiot, and thus another example of an unhelpful stereotype about men in comedies and kids' media. There's a sliver of truth to that, but I also think it misses the mark. Baloo isn't really an idiot. He's more of a savant: brilliant at his job, unsurpassed when he's allowed to follow his passion, and reasonably clever, alert and observant when he makes an effort and isn't just goofing off. Or: he can think and reason just fine, but he sucks at anything academic. That doesn't necessarily make him dumb.

Of course, the street-smart guy who sucks at book knowledge is a very common trope. TaleSpin is kind of like The Last of Us in this sense. It doesn't have an original bone in its body, but it uses classic ingredients so well you can't help respect the end result. The focus here is on craftsmanship, not innovation, and I kind of like that sometimes.

The reason this works is that TaleSpin gives every stock archetype enough layers to be interesting.1 This is especially true for Baloo, since he's the main character. And I think the single most interesting thing they do with him is almost laughably simple: he's allowed to not be a jerk.

It's kind of sad this is so revolutionary. Still, it's far too rare to find a character of this type who isn't a terrible person in need of involuntary redemption by an adorable tyke. How easy wouldn't it have been to have Baloo start the series as a gruff, bitter, spiteful, angry and self-centered failure2, who slowly (oh so painfully slowly) changes for the better when he has to take the ever cheerful Kit Cloudkicker (Alan Roberts and R.J. Williams) under his, ahem, wing?

I mean, I get it. There's a lot of mythic appeal to this trope. It's a great story arc, and it practically writes itself. That said, I have to admit I'm sick to death of these angry, spiteful dudes. Not so much because they're overused, but because they just weren't any fun to begin with. Who wants to spend two-thirds of a story with a raging asshole?

Baloo is way too laidback to be bitter. Why should he be? This guy lives in the moment. He doesn't have much in terms of money, but he has his dream job, his plane and his best buddy3, so he has no reason to mope. This makes him a million times more likeable than grumps like Joel, Charlie or Diane from the get-go.

Again, potential objection here: if this guy is so happy with his life, where's the conflict? Where's the room for growth? Doesn’t that make him boring and perfect? The TaleSpin writers are nothing if not master craftspeople, and as the series opens, they cleverly flip these strengths on their head to provide our hapless bear's fatal weakness and pull the rug from under him. To unpack that, we need to zoom out a bit and talk about the premise for the series.

Pulp adventure and the working class

First off, hat-tip to this well-made retrospective on the show by Tim Partridge, who raises similar points to what will follow in this section, and inspired me to look at TaleSpin from the perspective of work and money. Also worth a view for many other interesting angles I don’t have room to cover here, plus behind the scenes quotes and more:

TaleSpin ran for the standard three seasons, but it also had a four-part prologue miniseries that’s really more of a proper cinematic feature arbitrarily split into pieces. Watching it now after 35 years, I think Disney wasted a treasure here. This thing could easily have been the basis for one of their full cinema releases, and for my money every bit as good as the other animated classics from the 90s. The pilot (no pun intended), titled Plunder and Lighting (PL), is also useful for our purposes as a sort of baseline for the series. The purest, most purposeful vision of it, if you will. It’s an unfortunate fact that while PL and some individual episodes are very strong, there’s also a lot of chaff, random ‘stuff happens’ plots and inconsistent writing throughout the series’ run. In an ideal world, they should have kept the 20 or so good episodes and scrapped the rest.

The beginning of PL does indeed have our furry hero in a pretty good place. Again, unlike a lot of characters in this archetype, he’s not working like a maniac to fill a hole in his soul. He’s just a guy who really likes his job. In a surprising stroke of realism for a kids’ show, though, what he doesn’t like is boring stuff like bureaucracy and accounts. Baloo is a great pilot, but he’s also a sole proprietor, and he’s lousy at running a business. The story opens with some high adventure featuring his protege-to-be, Kit Cloudkicker (more on him later), but it soon takes a turn into semi-realism: Baloo hasn’t been keeping up with his payments, and now his beloved plane is getting repossessed.

His plane and cargo business are eventually bought out by an ambitious young businesswoman, Rebecca Cunningham (Sally Struthers), our third and final main character.4 This sets up one of the main conflicts of PL, and the classic unresolvable status quo of the series as a whole: Baloo’s goal is to earn enough money to buy back his plane and his independence, even as he gradually loses the desire to do so because he values Rebecca’s friendship and leadership. You know, as you do in these kinds of stories.

I think this focus on money and finances is pretty clever and interesting. TaleSpin owes a lot of its DNA to a genre and aesthetic that’s drenched in escapism, so I appreciate this unexpected turn to such mundane realities. Just as much as the Indiana Jones pulp adventure, it’s a story about work and working life. Baloo is a genius when it comes to flying, but that’s not enough. He has to find a way to translate that skill into actually making a living, in the real world of bills and expenses, even if simplified for the young audience.

What’s more, a lot of the episode plots tend to be framed in terms of work and money. We often see Baloo and Kit hauling cargo, even if these trips have a tendency to be setups for pirate dogfighting sequences. They spend a lot of time actively looking for work, and money is a constant motivation. They can’t afford to turn down obviously problematic jobs, and so on. All this adds a certain…I don’t want to say “realism”, since this whole show and universe aren’t realistic in the least. Maybe a certain believability, or a certain stylized grit that makes it a little easier to believe that this is a living, breathing world people have to fight to survive in, even our cartoon heroes. Of course the specter of the Great Depression is haunting the background here too.

It’s also a great way to ground the pulp aspects, and to gently politicize our characters. For example, I don’t think Indiana Jones ever has to worry much about finances. His job is pretty much only a device to get him into adventures, and he probably has tenure and a comfortable salary back home. Meanwhile, Baloo has a working class edge to him, while also being a kind of small business owner, or at least a partner in one under Rebecca.

All this makes for a surprisingly nuanced message: sure, it’s important to do something you love and are good at for a job. That love in itself won’t put food on the table, though. Unglamorous as it is, marketing and finances matter. Running a business is a skill in itself, and that’s where Rebecca comes in.

Well…at least in theory. She’s set up as Baloo’s perfect foil and partner, but it turns out she’s not nearly as competent at her job as Baloo. At least not with what we’re shown, but I suppose she could do a lot of the boring stuff off-screen. So yes, as far as I’m concerned Rebecca is by far the weakest link of the main trio. She also tends to end up in the “boring, obstructive authority figure” role when the boys want to do something irresponsible and pulp adventure-ish, which doesn’t do her any favors either. There’s room for a lot of potentially very interesting conflicts between her and Baloo, so it’s a shame she usually isn’t given enough nuance to realize it.

Who’s raising who?

The basic conceit for characters like the trio of grumps I made fun of above hinges on a simple arc: they start off as terrible human beings, but being responsible for a child drags them by the hair up the baseline of “functioning, non-sociopathic person”.5 Their flaw is extreme selfishness, or if you like, immaturity, whether it manifests as lack of empathy or lack of perspective. They’re incomplete as humans. One step up from the jerks, we get this archetype:

The idea is essentially the same, but this time the guy6 is a clown and a manchild rather than an intolerable jerk. When done well, as in this example, it’s a huge improvement. Still, this is where Baloo surprises in a good way. He’s not only not a jerk, he’s a reasonably “complete” person in balance with himself. Immature at times, sure, but not in the crippling Will Freeman7 manchild way. Also note that him becoming a surrogate parent to Kit doesn’t do anything to help fix the one issue his immaturity causes in his life, ie. losing ownership of his plane, so that’s another break with the trope.

In their usual tongue in cheek way, TVTropes calls this a “Children Raise You” arc. It’s the kind of thing that’s a lot of fun in fiction, but would be terrible in real life. A dysfunctional adult shifting so much of his or her emotional load onto a child isn’t great, to put it mildly. On the other hand, Baloo doesn’t need to be raised. He’s already an adult, even if a flawed one. Or: he starts the series at the baseline the Joels, Charlies, Dianes and Wills of the world manage to scrape their way up to by the end of their respective stories. The huge advantage of this is that it leaves him free to actually be a parent. Of course the responsibility makes him a better person too, but there’s never any question he’s the one raising Kit and providing him a safe, loving home rather than the other way around.

It’s true that this robs us of that deliciously cathartic arc of seeing a broken adult healed by the love of and for a wayward child. I think it’s more than worth it in this case, though. Instead of Kit “raising” Baloo, their conflict in PL runs on loyalty and trust, and after the climax, Baloo adopts Kit and that’s that. Just like how it’s disappointingly rare to see a married couple navigating their relationship after it’s consummated in (popular) fiction, it’s rare to see one of these arcs where they’re firmly established as father/son from the get-go and that’s not the issue.

So what is it that makes this silly cartoon bear’s particular kind of masculinity so healthy? For one thing, he’s playful, carefree and yes, even childish sometimes, but not to the extent it destroys his priorities (too much, anyway). Grouching aside, when it comes down to it he’s both a consummate professional and cares deeply about his surrogate family. He’s defined by his job and isn’t seen to have any hobbies or interests to speak of outside it, other than slacking off and drinking8, but he’s not consumed by it either, like a lot of dysfunctional men in fiction.

Tying in with the above, he’s very dedicated to his craft. He’s brilliant at what he does and knows it. This gives him an appealing sense of masculine confidence through physical action and a sense of mastery, without tipping over into smugness. It’s okay that he sucks at academics. His awesome flying skills more than compensate. I like this idea of a main male character being celebrated for his skill at a trade, in an age where it often feels like abstract, academic knowledge is the only thing that’s valued. Baloo isn’t neurotic, which also feels refreshing these days. He’s secure in his identity as one of the best pilots of his generation, and he knows he’s the one who actually creates the value his company needs to survive.

Another healthy aspect: Baloo is very affectionate and emotionally open without becoming mushy about it. We’re constantly given small reminders that he loves his son. The interesting part is that he’s almost always expressing it physically rather than verbally, so it comes across as “traditionally” masculine without being stereotypical or obnoxious. A surprising number of scenes throughout the show has him hugging Kit, picking him up, letting him sit on his lap and a lot of other small physical gestures of affection, often as background detail while the characters are talking about something else related to the main plot. Even their very first meeting in PL is physically based, even if that moment is more played for slapstick comedy than affection.

In any case, these constant little helpings of love go a long way towards reinforcing their relationship in a subtle way. As a bonus, they visually build the symbolism that Baloo is the big, strong one and the protector, while Kit gets to be a child in a way he couldn’t with the air pirates. They’re not equals, and they’re not meant to be. Unlike the bunch of dysfunctional Children Raise You pseudo-parents, Baloo is mature enough to bear (pun not intended) that responsibility with grace.

Baloo always has a choice. He’s never forced to have Kit around, nevermind parent him. In true About a Boy style, Kit is the one who initiates their relationship by stowing away on Baloo’s plane, but after that Baloo could ditch him at any point in the first half of PL with no consequences to himself.9 This also leads to an important twist on the usual Children Raise You formula at the end. These stories usually culminate in the final, crucial choice, where the adult character literally and/or symbolically says “I choose and accept you as my son/daughter”. Yes, there’s a pointed similarity to the structure of a typical romance here, with an “I love you” declaration at the end, often with a marriage proposal as the cherry on top. That’s of course not a coincidence: these stories are structural cousins. They’re both love stories, just about different kinds of love.10 Much of the pleasure of them lies in that long, twisting road, teasing us with the eternal question: will these characters dare to go all out and firmly commit to each other, to become family?

In a typical Children Raise You story, the adult is obviously in a position of power over the child. At the same time, though, the child tends to hold the moral power. It’s the adult who’s on audition, trying to earn the child’s forgiveness and through that redemption. That’s another reason it’s so tempting to make the adult a world-class jerk. Circumstance forces them together, often tragic and painful circumstance, but the adult keeps rejecting the child, even when the child clearly needs love and attention more than ever in his or her life. Finding an explanation for why someone who’s not a huge jerk would do this isn’t easy, so it’s a handy shortcut. Sometimes, as with Charlie and Diane in the earlier examples, the child they’re rejecting is their own biological son or daughter, and this present-day explicit rejection is a sort of cruel summary of a lifetime where every single day has been an implicit rejection of their child. The ending is so cathartic because it’s both the adult finally saying “I accept you”, and the child saying “I forgive you”.

TaleSpin subverts this nicely. Implicit in the above is the idea that the adult is deeply flawed, selfish and unhealthy. Or as I put in an earlier section, in need of redemption by an adorable tyke. Baloo doesn’t have to anything to apologize for. If anything, the ending to PL hinges on Kit apologizing to him, for convulted story reasons we don’t need to concern ourselves with here. He has the moral power all along, and he still freely chooses to adopt Kit. Even when it gives him a burden rather than redeeming him. While he does care deeply about Kit and wants give him a better life, though, there’s also something slightly darker and, to our twenty-first century eyes, uncomfortable at play here. As noted, TaleSpin is in many ways a story about work and working life, and in the thirties, these weren’t as hermetically sealed off from family life as they tend to be today. Which brings us to the other reason Baloo decides to adopt Kit Cloudkicker:

Passing on the trade

Baloo and Kit aren’t just father and son. They’re colleagues. Since he grew up with a group of air pirates, Kit is a skilled navigator, and so provides another essential skill for Baloo and Rebecca’s business. I like this idea a lot in theory. In a pulp adventure story like this, it’s not easy to find a way for a preteen boy to meaningfully contribute to the “mission” rather than just being along for the ride. At least not without going the somewhat predictable route of giving him magical powers, which wouldn’t fit in this setting anyway. It’s a clever idea, and it makes at least a little bit of if-you-squint cartoon sense that he’s precocious and talented enough to do this well enough for Baloo to have any use for him. Plus, in symbolic terms it’s a nice halfway between Rebecca’s academic focus and Baloo’s practical sense, so it helps show him as a sort of in-between point as the final member of the trio. Or as the ternary to resolve their binary, in Druid Revival terms.

So, what’s the problem? In practice, the show tends to forget about his supposed navigator job much of the time, and when it does come up, it’s mostly window dressing. A related problem here is that much of the conflict in the pulp action parts of the show tends to come in the form of dogfights and/or death-defying piloting stunts, and those are fully in Baloo’s half of the field. Of course it’s also harder to make visceral action and stakes out of a kid looking at a map, but I think they could have found ways if they really wanted to.

On a more subtle note, navigating obviously demands a firm grasp of geography. And that’s a problem when the show doesn’t really want to commit to much of a firm geography for its setting, to the point that even the Higher for Hire dock moves around from episode to episode depending on the animators’ whims. And of course Kit’s navigation skills are of no consequence at all when the show goes into sitcom or “random stuff happens plot” mode, which is one more reason I think they’d have done better to stick to their core premise a la PL.

Or maybe there is an in-universe explanation after all, if we reach a bit: maybe his heart isn’t quite in it, since Kit’s dream isn’t to become a world-famous navigator. In a predictable but effective way, he’d much rather become a master pilot, like a certain big bear. That’s another reason for him to come along on so many of Baloo’s jobs rather than hanging out at the office, picking up an age-appropriate hobby or getting an education.12 Kit is obsessed with planes, both in a piloting sense and a trivia sense, even if he’s never shown as especially interested in the nitty-gritty mechanics of their engines. Although Baloo is presented more as a savant at the art of piloting rather than a plane nerd as such, Kit's interest in all things aeronautical is what makes Baloo first notice and care about the kid in more than a surface-level way.

So what we have here isn’t just a family. It’s a family business. Both parts blend together seamlessly. That’s a beautiful thing, but also culturally dissonant from our vantage point almost a century later. The show doesn’t want to dwell on it too much, but Kit has had a very harsh childhood by our standards. Apparently orphaned early, he was taken in by the funny cartoon equivalent of a street gang and raised by thugs. He’s routinely had to help make a living by robbing people at gunpoint. Indeed, stealing is the very first thing we see him do in the show, even if he’s turning his larceny skills on his own pirate boss. Since TaleSpin is a kids’ show, this heavily defanged by a) making the thugs ineffectual buffoons and b) a firm aversion to ever having Kit angst about it.13 That doesn’t make it go away, though. The implication still haunts the back of our minds, especially for adult viewers.

Even after he’s adopted by Baloo, he’s still in the same dynamic. Kit still has to work for his family and actively help earn a living. This is where the dissonance comes in: much of what he does in the show could be read as child labor by our standards. If you wanted to be extra uncharitable, you could accuse Baloo and Rebecca of exploiting a foster kid who has no one else for free, skilled labor. As much fun as it can be sometimes to read silly cartoons in a maximally egdy way, though, this obviously misses the mark. If nothing else because this is the (fictional and sanitized) 1930s, and by that standard he’s getting a pretty good deal.

That’s the flip side of that unbounded adventure-playground aspect I talked about in the beginning: this world was raw, anarchic and unconstrained by our standards, for good or ill. You could get away with adventure, but you could also get away with things we’d rather not let anyone get away with now. Such as, say, treating twelve year olds as working adults. Legendary curmudgeon James Howard Kunstler, who I’ve cited in these essays before, has a nicely pithy saying that skewers our modern world: “anything goes and nothing matters”. The thirties certainly had the “anything goes” part down too, just in a different way. Did things matter more? Maybe in the sense that working often was a matter of literal life and death, at least. Even filtered through TaleSpin’s cheery cartoon lens, Baloo and Rebecca have to make their way in a very hostile world with no safety net. Why wouldn’t they enlist a clever, skilled twelve year old in their business?

Furthermore, the show presents this as liberating rather than exploitative. This is partly because the 1930s family drama aspect crashes into the escapist pulp adventure aspect here, and in a show like this, the pulp adventure ultimately has to win. Sure. That’s only fair. There’s more to it, though: the real reason this is uplifting rather than depressing is that Kit isn’t an indentured servant. He’s a young man being apprenticed to a master to learn a trade. A craft. He’s the last link in a long chain reaching back to the medieval guild system, which had its horrors, but also had some very valuable aspects we’ve mostly lost in our day. At least in my opinion. Without turning this already long and rambling thing into a political essay as well, I think we could do with more apprenticeship and less academization of everything here in the twenty-first century. Again without neglecting a lot of cultural changes based around trying to understand and emphatize with children rather than treating them as property, which I personally appreciate deeply.

Unlike a lot of children today, Kit is allowed to contribute meaningfully to his family’s survival and thriving. He’s given real, meaningful responsibility. And he gets to learn something practical, nuanced, artful and immediately useful from a master. That’s a far cry from 13 years of academic industrial schooling, isn’t it? Of course, TaleSpin goes beyond this and sweetens the deal by also having him take part in absurd cloud-surfing action setpieces, treasure hunts and dogfights, because it’s a pulp adventure cartoon for kids as well. The point still comes through.

Portraits of a healthy masculinity

The male characters do come off much better in this show, in comparison to the somewhat-caricatured Rebecca. While both Baloo and Kit have a lot of traditionally male qualities, both negative and positive, they’re not toxic in the least. And certainly not any kind of mirror of the real 1930s. I’ve touched on Baloo’s emotionally healthy outlook above, but crucially, it doesn’t rob him of his toughness and tenacity. Compare this to, say, the current (as of 2024) iteration of my old favorite Doctor Who, which as I hear it has a very emotionally unbalanced male protagonist14. There’s plenty of people who’ve made it their mission in life to criticize the likes of modern DW, so I won’t get into the specifics here, but I do think it’s an interesting contrast to Baloo and Kit back here in 1990 reflected in the wan light of the 1930s.

Baloo escapes the classic “workaholic emotional black hole” trope by being nurturing both as a provider for his son and in more “modern”, emotional ways, as I talked about earlier. He represents the best of both worlds, as a model of healthy masculinity. He does have a whiff of the "irresponsible manchild” aspect to him, but it’s only really a problem in the hands of the lesser episode writers. At his best and more nuanced, as in PL, he comes across more as laid-back and occasionally lazy, but with his head in the right place when it really counts. Another interesting aspect here is that with how the show is structured, PL is the only place where he can really go through any sort of arc. After that both he and Kit are essentially static characters, their dynamic set in stone. Since there’s so much else going on there, and because the writers are smarter, Baloo isn’t subjected to the full Children Raise You arc of learning responsibility. Instead, he’s shown at the start of the series proper as having learned, but it’s not such a drastic change, because he didn’t have that far to go to begin with.

On his part, Kit is also surprisingly nurturing. At first glance he’s a very typical boy hero who does all kinds of action-y boy stuff: piracy, air-surfing, nerding out about planes, helping out on the sidelines during dogfights, escaping jails and so on. In a very deft touch on the writers’ part, we also see him immediately bonding with Rebecca’s young daughter Molly (Janna Michaels) as soon as he meets her in PL. Just like how it would have been so easy and so predictable for the writers to set up a bogstandard “will they or won’t they” romance dynamic between Baloo and Rebecca15, they could have had Molly as either a snarky preteen around Kit’s age who constantly bickers with him, or as a love interest to enable ten episodes’ worth of iCarly-style wacky sitcom hijinx. Instead, the writers had the wisdom to make her much younger, so Kit ends up as a big brother figure she looks up to and leans on. In a sense, he gets to “pay forward” the love he receives from Baloo. Most importantly, it brings out the absolute best and even, dare I say it, noble sides of him as a young teenager, rather than the worst and cringiest ones we’d have seen if Molly had been a dumb modern kid-com-style love interest. As a bonus, her age keeps Molly mostly on the margins other than in the occasional spotlight episode, so the show can focus on its core cast of Baloo, Kit and Rebecca most of the time.

He’s also very emotionally supportive of Baloo. Not in the unfortunate implications sense that Baloo leans on him emotionally, but more that he’s the one who reminds Baloo of his worth during the really serious crises where his adoptive father loses his nerve. Because they’re used sparingly, and because the show goes out of its way to show that they do have a healthy dynamic where it’s usually the other way around, it works very well.

The writing in TaleSpin isn’t as obsidian sharp as something like The Adventures of Pete and Pete. Still, at its best it has real heart, tons of charm and enough nuance to be worth watching even as an adult, if you like this sort of thing. It has lush, hand-drawn art of the kind we can only dream about these days and a brilliant dieselpunk world that’s always a treat to step into. All the elegance, adventure and class of the thirties is on display, carefully scrubbed of the insane cruelty and poverty. And maybe most importantly, it reminds us of what we knew all along: you can be brilliant even if you’re not an academic. You can be a warm, nurturing foster father even if you’re also a tough guy who flies planes and punches people. You can have occasional crises of faith without walking around in a constant haze of neurosis. You can be a rambunctious, adventurous boy and an excellent babysitter. Traditional masculinity isn’t the only game in town, but it’s also a healthy, warm, sane masculinity, if we allow it to be. It’s kind of a shame we might need an early 90s cartoon to tell us that, but, well, here we are.

Or if you prefer, those are a lot of words to say that I’d love to see more men and dads like Baloo in popular fiction: embodiments of a genuinely healthy masculinity.

Well, maybe not as much with Rebecca, but it does depend heavily on the writer

To be fair, he does start out as kind of a failure in spite of his enviable skills, but he’s not the obnoxious, self-pitying sort of failure. Not often and not for long, anyway

Another Jungle Book expat, Louie (Jim Cummings), a recurring support character who mostly but not only encourages Baloo’s slacker tendencies

Some might want to count pirate leader and arch-villain Don Carnage (Jim Cummings) as a main character too, especially since he’s taken on sort of a memetic afterlife in fandom long after the show ended. He’s pretty one-note comic relief, but a good one, mostly down to Cummings’ performance

You could make a good case Joel is still pretty damn sociopathic all the way to the end and beyond, though

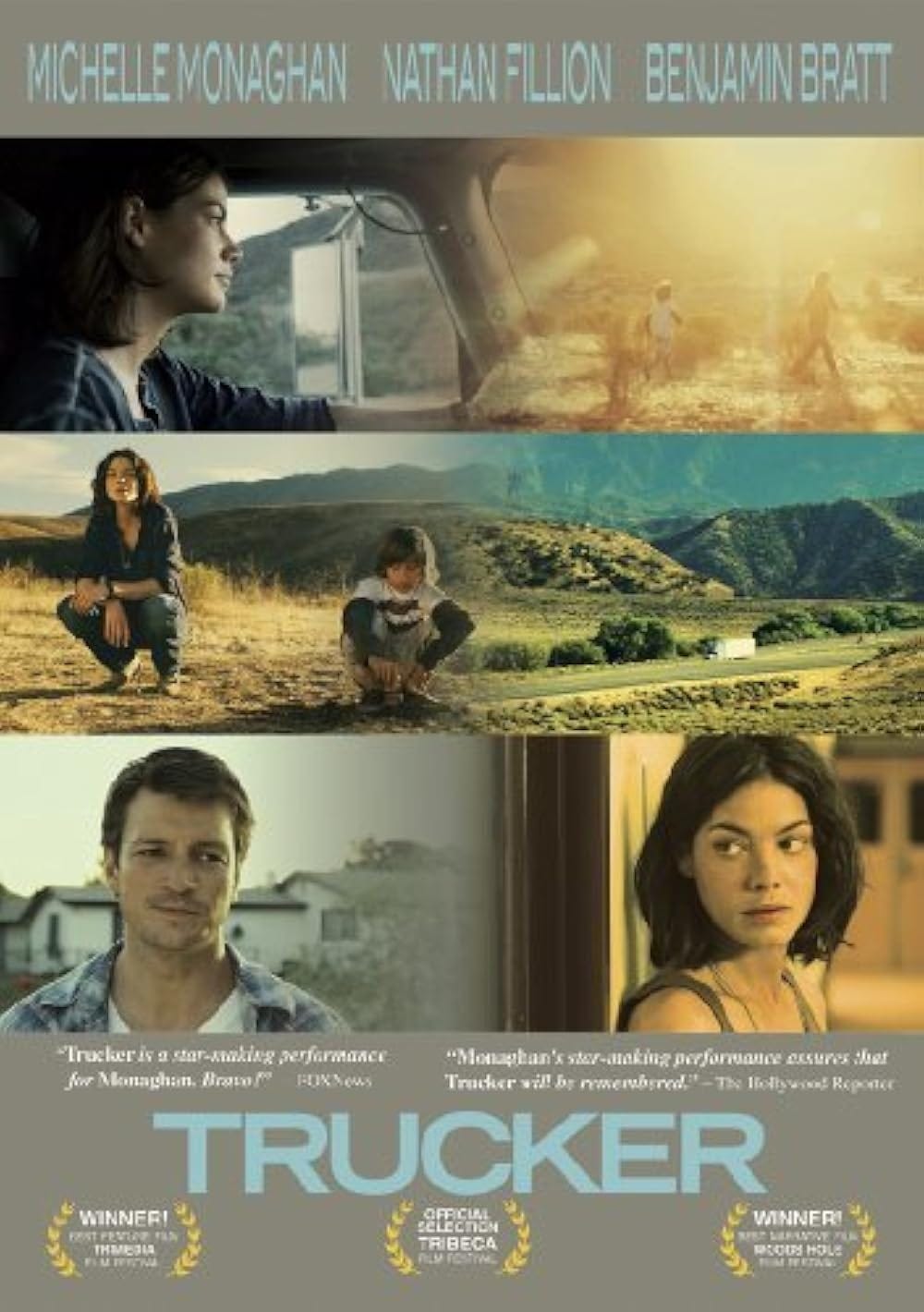

It’s nearly always a guy. In my extremely unscientific estimation, father/son is by far the most common of the four possible variants of the trope, followed by father/daughter in close second. The latter is especially popular when combat is involved, compare this TVTropes page. Mother/son shows up occasionally, as in our Trucker example, while I’m pretty sure mother/daughter is dead last. I suppose deadbeat moms are still kind of a taboo to portray even now

Yes, that’s an extremely on the nose name. Blame Nick Hornby for that one

Usually super-fancy milkshakes that totally aren’t a transparent stand-in for alcoholic drinks, honest

Other than missing out on the services of a free navigator, anyway

I think it’s interesting that these two kinds of love play out so similarly in fiction terms, in spite of the vast and important differences between these kinds of relationship. Meanwhile, it’d feel pretty unnatural (but not impossible) to structure a “friendship love” story this way, I think

Actually, as sweet and stock photo-like Goyo and Jackman look together here, I kind of hate how this movie handles its Children Raise You arc and how it squanders so much of its potential. To the extent I might write an unnecessarily long essay explaining why sometime :P

To be fair, Kit is actually shown attending school at one point, even if this is mostly in service of the dumb sitcom plot of the week. It does raise all kinds of interesting implications the show isn’t terribly interested in dealing with, though. Like, is Baloo homeschooling him while they’re off on pulp adventure expeditions in the Himalayas?

A glum “I don’t have any folks” early on in PL before the subject is swiftly dropped is about all we get. Then again, apparently they only settled on Kit’s backstory late in development of the show, so that’s another reason it comes up so rarely

I haven’t been able to bring myself to actually watch it as of writing this, and I’d also very much like not to give modern Disney any money if I can help it

Most of the time, at least. Unfortunately some of the less capable episode writers do resort to this crutch a few times, but it never sticks

Great essay! My only previous knowledge of TaleSpin comes from it being in the same 'style' as the Ducktales adventures era, but after reading through your essay, it sounds pretty fun, and I enjoyed how you were able to connect it to its themes and also show what it didn't do. It is so astonishingly rare to find good parental male role models in any children's media.

Enjoyed reading through this one a lot!